I was excited beyond measure when I heard Chitra Banerjee Divakaruni was coming up with a book that was a retelling of the epic Ramayana. Her book ‘Palace of Illusions’, the retelling of the Mahabharat through the eyes of Draupadi, made for an interesting read and I wanted to see how she would present Sita now.

But I was skeptical about how she would approach the story. Having read her other books, I know for a fact that she appreciates and favors strong women characters – but strong in the more obvious and visible ways. Even in the male narrated stories of Mahabharat, Draupadi is portrayed as an irate and ambitious figure. She is, someone I would call, a protofeminist because for the most part there are indications of her dissenting and refusing to comply with norms. She was quite a willful person, for her time that is. As Divakaruni’s books go, her being the heroine in Palace of Illusions was very fitting.

Sita, on the other hand, is a figure set as an ideal example of how women should be, at all stages of their lives. But these ideals are those that have no place in the contemporary world. Compliancy, tolerance, and endurance, for which Sita is praised for, are taken as signs of weakness today. By the author’s own admission, Sita is meek and docile and a character that suffered without questioning or even protesting. Sita is good but good at the cost of her own self and in today’s world self-love is something that’s given priority over other virtues.

Sita thus made for an odd choice of character for Divakaruni. But she has attempted to write her own version of the story, in a completely different light, and has thus changed a ‘dutiful’ Sita into someone we haven’t met before. The Forest of Enchantment’s Sita is fierce, eloquent, and unbending. She is a skilled warrior who can hold a fight of her own, a wise tactician who people (including Ram) flock to for counsel and a leader with a shrewd sense of justice.

Lumbini govt's policy and programs aim to discourage migration...

The story of Ramayana is not new to us, we know it in great detail and even those who don’t can at least tell what follows what. The book picks up from the holy sage Valmiki presenting his finished work of Ramayana to Sita at his hermitage. He asks her to be the first reader of his epic and Sita agrees. She spends a good two nights devouring the volume and, upon finishing, the sage asks her what she thinks of it. Sita praises his writing and appreciates his understanding of such a complex tale but she does so with barely concealed anger. She is furious at how the narrative dismisses the important roles played by women and only pays its share of respect to men.

So she decides to write her own version of events in what she calls the ‘Sitayan’. Before her marriage to Ram, Sita is Mithila’s beloved princess who, if norms and customs allowed, could have been the next ruler of the kingdom. She is intelligent and learned just as her mother Queen Sunaina, who is an important figure in Mithila’s court. Her marriage to Ram is a grand affair and, to the besotted Sita, one of the best occasions in her life. Sita comes across as any protagonist does – a highly intelligent character, admittedly special but not in any way most of us aren’t. Maybe that was exactly what she was. She giggles with her sisters, loves mischief, and turns her nose at traditions.

Then the book takes its deep dive to the darker sides of the epic: banishment from Ayodhya, the 14-year exile, her abduction and capture in Lanka, Ravan’s defeat, Sita’s humiliating test of purity, the return to Ayodhya, her second banishment, the birth of her sons and her ultimate demise. But the sequence of events isn’t important here, it has been told too many times.

Scattered all over the retelling are stories of the free spirited and fiercely loyal Urmila (Sita’s younger sister and Lakshman’s wife). Kaikeyi too isn’t relegated to the role of a selfish mother and she is given her share of credit for being an excellent charioteer and swordswoman. Mandodari (chief consort of Ravan) is more than a demon queen but a discerning leader with depth to her character and infinite compassion for her subjects. Her own mother, Sunaina, is an intelligent and exceptionally well-learned queen who is perhaps a better ruler than King Janak.

Then there is Ahalya, the beautiful wife of Sage Gautama, who was cursed for an infidelity she committed because she was tricked. Ahalya is a character often spoken about with pity but Sita’s Ahalya is a striking personality, one whose very presence evokes respect. These are women as Sita sees them or rather wants to see them.

Then there’s Ram himself. The Forest of Enchantments is, in some ways, a tragic love story. The language makes scant attempts to glorify the characters, not even the celestial incarnation ones. The Ram you find here is a conflicted youth who is forever questioning his actions and holding himself to such strict standards of righteousness that you almost feel sorry for him (but not really, it’s self inflicted). Ram is human here, with his own faults and doubts, and not the deity we are constantly being reminded he is. And despite her love for Ram, Sita questions many of his actions and condemns them.

Now this is not to say that this is the greatest book. I would probably think twice before recommending this to someone. The writing, at times, fails to deliver the sheer impact of particular events. And although the women in the story are the prime focus, there are a number of characters who are important in Sita’s life but who aren’t mentioned much in the book. Had I not known of them before reading the book, I would have had a hard time placing them in the story arch. But this is not to fault the author’s writing. She has a great writing style, just that that narration feels abrupt and inadequate at moments.

In retrospect, Divakaruni didn’t change Sita to fit her own narrative. Sita probably is everything the book’s version paints her to be. This Sita may not have had a place in the traditional narratives of her being the epitome of womanhood (and inferring to all qualities of servitude and endurance) but this Sita exists. Maybe Sita, contrary to what I believed, is exactly the kind of character Divakaruni favors. Perhaps, she was stronger than they made her out to be and for this reason alone this book deserves to be read. Sita deserves to be looked at with a different perspective.

In the author’s note, Divakaruni says, “May you be like Sita”. In another time (before reading this book, that is) this statement would have irked me. Now, I don’t mind anymore.

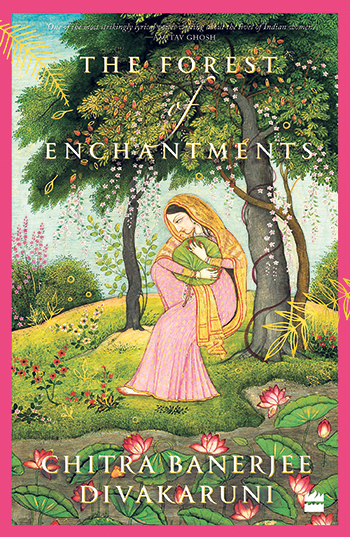

The Forest of Enchantments (Chitra Banerjee Divakaruni)

Language: English

Published: August 2019

Publisher: Harper Collins India

Pages: 372, Hardcover