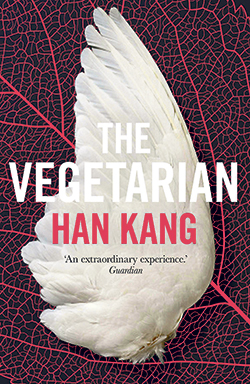

The Vegetarian, a novel written by South Korean writer Han Kang, was published in 2007. Its English translation, however, was made available only in 2015, following which it has managed to make a big global impact. The novel is actually based on a short story Kang had written back in 1997 called ‘The Fruit of My Woman’. The novel follows the story of a part-time graphic artist and homemaker Yeong-hye whose life takes a drastic and dramatic turn after a nightmare results in her becoming a vegetarian.

The novel is in three parts, ‘The Vegetarian’, ‘Mongolian Mark’ and ‘Flaming Trees’. The first part is narrated by Yeong-hye’s husband, Mr Choeng. In the very first line of the novel, Mr Choeng describes his wife as being “completely unremarkable in every way” and after reading a few pages, it’s evident that he sees and wants Yeong-hye to be a submissive housewife who will tend to his needs no matter what.

And for a while, this is exactly what happens. But one day, this thin sheet of seemingly ordinary lives comes crashing down as Yeong-hye decides to rid their entire house of meat and turn into a vegetarian (more accurate term would be vegan – as she doesn’t eat dairy or use leather either). This, of course, doesn’t sit well with Mr Choeng who was used to having his say in the house. Even after repeated rebukes, Yeong-hye is adamant to remain a vegetarian and you can sense Mr Choeng’s frustrations.

This, I think, was a direct but perhaps a little dramatic reflection of the patriarchy that’s still embedded in the Asian culture where women, rather than being unique individuals, are expected to exist only in relation to their husbands or the men around them. When Yeong-hye refuses to eat meat in a special meeting when dining with Mr. Choeng’s boss, we hear him victimizing himself – disgusted by how Yeong-hye brought shame to him by not eating food offered by his superiors as well as not keeping up the façade of being ‘extra’ grateful and social.

Lumbini govt's policy and programs aim to discourage migration...

At this point, as a reader, one is rooting for Yeong-hye in her quest to do something by herself, even though it’s directed by a nightmarish dream of raw flesh and blood. This simple act of choosing to not eat meat turns Yeong-hye’s life and of those around her into this violent, brutal mess – especially when her father tries to force a piece of pork into her mouth and, in revolt, she cuts herself.

The second act of the story is narrated by Yeong-hye’s brother-in-law whose name we never learn. All three parts of the novel is narrated by the people around her – all clouded by their own prejudices and motives. Thus we never truly know what is actually going on in Yeong-hye’s head. As the story progresses, she speaks even less and less and we have to come to our own conclusions through her actions as described by others, which is confusing yet fascinating at the same time.

During the first half, we see Yeong-hye as a woman who finally decides to do something for herself, refusing to conform to ideas of her husband and family. However, by the second act, Yeong-hye has grown anorexic and pale and has become secluded and vulnerable.

Yeong-hye’s brother-in-law, on the other hand, becomes obsessed with her when he learns that she has a Mongolian mark and he wants to turn her into one of his artistic endeavors. He manages to convince Yeong-hye and in the process decorates Yeong-hye’s body with flowers. We also see Yeong-hye refusing to get rid of the flowers in her body, telling her brother-in-law that they have put an end to the nightmares. We also come to know that Yeong-hye loves to sit naked, facing the sun as if she were a photosynthesizing plant.

Yeong-hye’s delusion escalates even more during the final act of the novel narrated by her sister In-hye. She stops eating altogether, stands upside down pretending to be a tree and, at one point, is found standing in a forest “soaked with rain as if she herself were one of the glistening trees”.

We realize that Yeong-hye wants to give up being a human all together – as we leech off of the earth, are abusive and brutal with one another and are, as a whole, selfish beings. Yeong-hye was abused by her father as a child, refused a sense of individuality as a wife and cheated out of an active choice she made. Nearing the end of the novel, Yeong-hye whispers to her sister, “I’m not an animal anymore” and that leaves the reader with a sour and heavy feeling.

The book can be interpreted in so many ways and I think each person’s interpretation differs in relation to his/her own personal experiences in life. For some, it may be about a woman’s struggle to do as she pleases or perhaps a satire at the still existent patriarchy. However, for me, I think the book has more to it that just ideas of choice or social issues. The book questions the very foundation of humanity itself as we see in the end Yeong-hye rejects the very idea of humanity, actively choosing to live as a plant.

The book is a phenomenal read. It’s gripping – bordering between intimidation and fascination. Kang’s descriptions are vivid – her descriptions of Yeong-hye’s silences manage to thunder in one’s mind. The Vegetarian can also be a little disturbing which is why, even though it’s a slim volume, we suggest you take your time with it.

Fiction

The Vegetarian by Han Kang

Translated into English from Korean by Deborah Smith

Publisher: Portobello Books

Published: 2015

Pages: 183, paperback