Nepal’s hills and mountains which once captured the imagination of the West as the land of Sangri La stand on the precipice geographically, politically and demographically

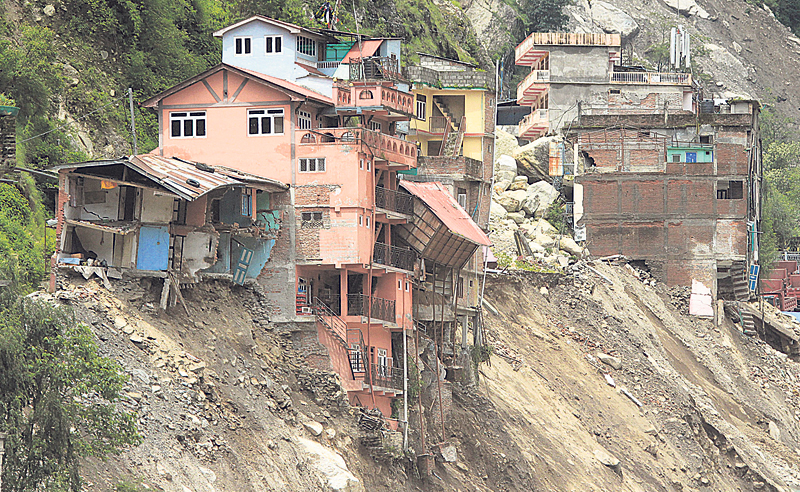

Sindhupalchowk district has succumbed to natural disaster yet again. This is the third disaster to hit the district in the northern frontier in the third consecutive year. Landslides in Jure killed more than 156 people and rendered hundreds homeless in 2014. Last year’s devastating earthquakes killed about 4000 people there. Glacier outburst, beyond China border, last month swept away about 100 houses in bordering towns completely disrupting what used to be Nepal’s only functioning road network to China—the Araniko Highway. Landslides have wrecked havoc in virtually all hill districts. Floods have inundated settlements in the Tarai plains. On an average 111 persons are killed and 14303 are affected by landslides and flood in Nepal every year.

I begin with reference of Sindhupalchok not only because it is my home and the district with the largest distribution of landslides (523, according to a report of International Centre for Integrated Mountain Development (ICIMOD)) but because it also represents the vulnerability of other landslide-prone hill districts. I discuss the woes of country’s 63 hill districts (including but not limited to landslides and floods) and reflect on how they are tied to the sorrows of Tarai plains. Perspective will be that of the hill, intentionally.

Food insecurity

Nepal’s hills are first casualties of food insecurity. The World Food Program reports put Karnali as the most food-insecure region. But most hill districts do not produce enough to feed their inhabitants even for six months. Imported rice from India and Tarai plains supplement their dietary needs. Part of the reason is topography. The soils in hills—mostly rocky, clayey, sandy and gravel-like—are not fertile. Land is fragile. Even if the farmers expend all their energies for the best possible farming, very little grows. Wildlife hazards add to the troubles. Monkeys, bears, rabbits, porcupines, wild pigs and crows destroy the crops in the fields close to the jungles. This is why a number of farmers have given up farming in villages (I have dealt with farming difficulties of hilly villages in an article titled “When mother earth speaks,” Republica, July 6).

Changing food habit has deepened the problem. Most people no longer eat traditional food. Locally produced millet, maize and buckwheat used to fulfill dietary needs of the rural populace in the past. People ate dhindo, grew vegetables in abundance and kept cows and buffaloes. This is not the case today.

As hill and mountain lands have little access to irrigation, monsoon dependent paddy cropping is declining fast. Villagers prefer to keep their land barren and purchase imported rice for consumption instead.

Nature’s wrath

The hills and mountains are highly vulnerable to water induced disasters, mostly landslides. This year alone a number people have been killed and displaced (see the graph above). Eighty percent of Nepal’s landscape is mountainous, which means they are prone to landslides. The average number of small and large landslides in Nepal is as high as 12,000 per year, according to ICIMOD. Hills account for almost all of this. Tarai, which constitutes 17 percent of Nepal’s land area, battles with floods every year.

Save the wetlands

Demographic decline

The above mentioned difficulties have led to depopulation in hills and mountains. Until 1981, Nepal’s hills used to be the most populated area. Hills had 71, 63065 population compared to 65,56828 in Tarai until 1981. A decade later, Tarai population outnumbered hill population. According to 1991 census, hill population had declined to 53.3 percent from 64.8 percent, while Tarai population shot to 46.7 percent from 35.2 percent from 1952 to 1991.

Fast forward to 2011, 27 of Nepal’s hill and mountain districts have shown a negative population growth. According to the latest census, hill population accounts for 11,212,453 while Tarai has 13,318,705 populations. Economically active population has deserted the hills and mountains and left either for Kathmandu Valley or Tarai. Some hill districts have witnessed an exodus of more than 50 percent of their population. If this trend is allowed to continue, demographers have already warned, more than half of hill districts could be nearly empty in the next 50 years. As hills empty, its traditional economy, vegetation and dairy farming suffer. The practice of keeping Himalayan cows and sheep is declining.

Burden in Tarai

On the other hand, Nepal’s plains, which constitute only 17 percent of the land, are accommodating more than 50 percent of country’s population. Population density in Tarai plains has increased to such an alarming level that lands are being converted into concrete jungles. Most fertile lands in districts like Jhapa, Morang, Chitwan and Makawanpur are being lost to land plotting.

As for flooding, most rivers that sweep off or inundate the lands in the plains originate from or flow through Nepal’s hills and mountains. Arun, Tamakoshi, Sunkoshi, Budhigandaki and Karnali, for example, sweep the debris down to the south during monsoon floods elevating the river basins in Tarai plains, which is one of the causes for flooding and inundation.

Farming difficulties, combined with harsh terrains and lack of development in the hills have pushed millions of Nepalis to migrate to Tarai plains. But migration does not change the fate. When it rains heavily up in the hills and mountains, people living in the Tarai have to lose sleep.

Another factor that spreads terror in the plains during the monsoon lies across the border. Locals of the most affected areas like Banke and Saptari have been complaining every year how building of dams, embankment and high roads by India along the border lines (along no-man’s land as well) have contributed to flooding and inundation in Nepal’s side.

Experts corroborate. Professor Hemraj Subedi recently told a national daily that barrages and dams built in Indian side, following various water treaties with India, Koshi (1954), Gandak (1959), Tanakpur (1991) Mahakali (1996), have contributed in submerging Tarai plains during the monsoon, while letting no water to trickle inside Nepal when it is needed the most for irrigation. “The dams India has constructed along areas from Mechi in the east to Mahakali in the west have put a number of Nepali lands in high risk of floods,” he said.

Political leaders who represent the flood-prone districts of the plains respond to the tragedy with comfortable silence. To raise the issue with Indian authorities, in their reckoning, is to commit a grave offence. When pestered, they say this is a bilateral issue and needs to be settled diplomatically.

Hill and politics

Nepal’s hills are victims of politics in their own ways. Hills provided formidable support to politics in Kathmandu in the past. The hill population (exclude feudal lords and rulers) did what rulers in Kathmandu wanted it to do. Lack of education, transportation and communication network made it impossible for hill settlers to alter politics in Kathmandu.

Nepal’s hills began to receive international attention only after the country opened up to the outside world in the early 50s. So our hills and mountains became something to be seen and written about for the international audience for the first time.

Exotic and breathtaking views would not change physical realities. Development of road networks and electricity at the fastest pace would have helped transform the hills during the 70s or even the 60s. But king Mahendra encouraged hill population to migrate to Tarai plains. The period of his rule witnessed the massive migration of hill settlers towards Tarai.

Historical references show Mahendra was more concerned about Tarai-Hill integration. Division of country into 14 administrative zones—each bordering India and China—can be taken as its example. But it is also argued that Mahendra’s decision behind resettlement in Tarai was triggered by his fear of Indian incursion. Madheshi leaders call it “internal colonialism” foisted on Madheshis by hill rulers.

It would be a mistake to say that no attempts had been made to change lives in the hills.

During the heydays of Panchayat, the king had made it a point to make a long entourage along the hill districts every year to listen to the people and to devise development plans accordingly. Back to the Village National Campaign (1967-1975) had been launched to “direct development efforts to rural villages.” Civil servants and students from the cities were sent to live in rural communities and participate in development works and serve as teachers in village schools. But this noble campaign did not continue for long.

“The regime discontinued this noble initiative, when Panchayat stalwarts sensed that the system was producing opposition within Panchayat,” Gobinda Adhikari, a senior journalist, told me during a recent conversation.

Another initiative that could have made a far-reaching impact in development of hills and mountains was the National Development Service (NDS), which was introduced during the early 70s. This program encouraged educated youth to reach remote corners of Nepal’s hills and understand the development difficulties. It required all Master’s degree students to dedicate one year of their study to serve in the rural communities.

It was perhaps the first social development experiment for Nepal. Predictably, NDS became a hallmark of development and modernity within no time. Both the participants and the beneficiaries of this program rue its discontinuity. They say the program generated awareness among people and became a threat to the Panchayat regime. After the 1980 referendum, both the government and the political parties found an excuse to discontinue the program. “Politics led to the death of this initiative as well,” Adhikari, who also served as a NDS volunteer during the 70s, said.

Political change of 1990 raised political awareness among the hill population. More people enrolled in school than ever before. At the same time, people also started to leave the hills. Depopulation of the hill also started from this point. Ironically, Nepal’s hills were hotbeds of revolution. Maoist leaders started armed struggle against the state from the western hills. They live in the capital today, one reason for their neglect of the hills.

In the post-federalism era, hills and their dwellers are characterized as agents of status quo, the exploiters of Madheshis and Tharus. So when someone advocates on behalf of hills and its development, there is increasing risk of that person being tagged as Mahendrabadi (follower of Mahendra) and a hill nationalist. But that is beside the point here. The hard truth today is Nepal’s hills and mountains are facing three serious challenges: population decline, food insecurity, and natural disasters.

Attempts are being made to further isolate the hills. There is a demand for making population the only basis in determining electoral constituencies. Which, if and when happens, will mean much less representation from the hills in Nepali politics. Thus, Nepal’s hills and mountains which once captured the imagination of the West as the land of Sangri La stand on the precipice geographically, politically and demographically. So what can be done to save the hills and to retain the population there?

Way forward

We need to get the people to live in the hills for they are the best place for human habitation, in terms of climate and vegetation. But how can it be done? I had approached Dr Baburam Bhattarai, the author of The Nature of Underdevelopment and Regional Structure of Nepal: A Marxist Analysis, with this question. He made a number of recommendations. He admitted that Nepal’s hills have become inhospitable. You just cannot say to the people to go back to the villages, he said. “We need to lift the rural poor from the traditional subsistence based farming and guarantee them employment. We must begin by building basic health and education infrastructure and provide them quality education.” Without this, he said, “it will be meaningless just to ask people to live in the hills. What comes from agriculture is not enough to feed the family even for six months.”

Then he floated a broader development proposal. “We must end the scattered settlement and start the compact settlement in safe areas. We should not allow the people to live over the precarious hills.” Another solution, according to Bhattarai, who is also former prime minister and chief of Naya Shakti, is to lessen the number of people dependent on agriculture. “We must not keep two third population of the country dependent on agriculture. We need to bring agriculture-dependent population to ten to 20 percent from existing 60 percent,” he reasoned.

But people also need to be saved from landslides and floods. Laxmi Dutt Bhatt, Ecosystem Management Specialist with ICIMOD, insists on the need for proper environmental assessment before any infrastructure projects are carried out in hill areas.

He recommends “proper selection of species [of trees] with deep root system to control landslide” and advocates for “watershed management/basin level approach” to ensure “environmental protection and development together.” “Our development plans are mostly sectoral,” he said, therefore, “we need to take holistic, intersectoral plans” to identify the critical areas.” All this makes perfect sense.

Indeed, Nepal’s hills can be made livable and lives can be saved. For this, however, a hope should be generated that life in the hill villages can also be comfortable. Completing the mid-hill highway as soon as possible will instill this hope. If we could have completed the north-south highways, which have been under discussion from as early as Panchayat eras, hills would have been transformed by now.

Nature has placed us on such situation that what happens in the hills and mountains have direct bearing over population and land across the country. Prosperity and wellbeing in one region depends on prosperity and wellbeing of other. This interdependence should not be broken. Reviving life in the hills is a tall order. But giving up on it will be even more dangerous. There are a number of countries in the world with topography like ours. They have managed their development and safety well. Yes, it will be costly and difficult. But this is how our country is like.