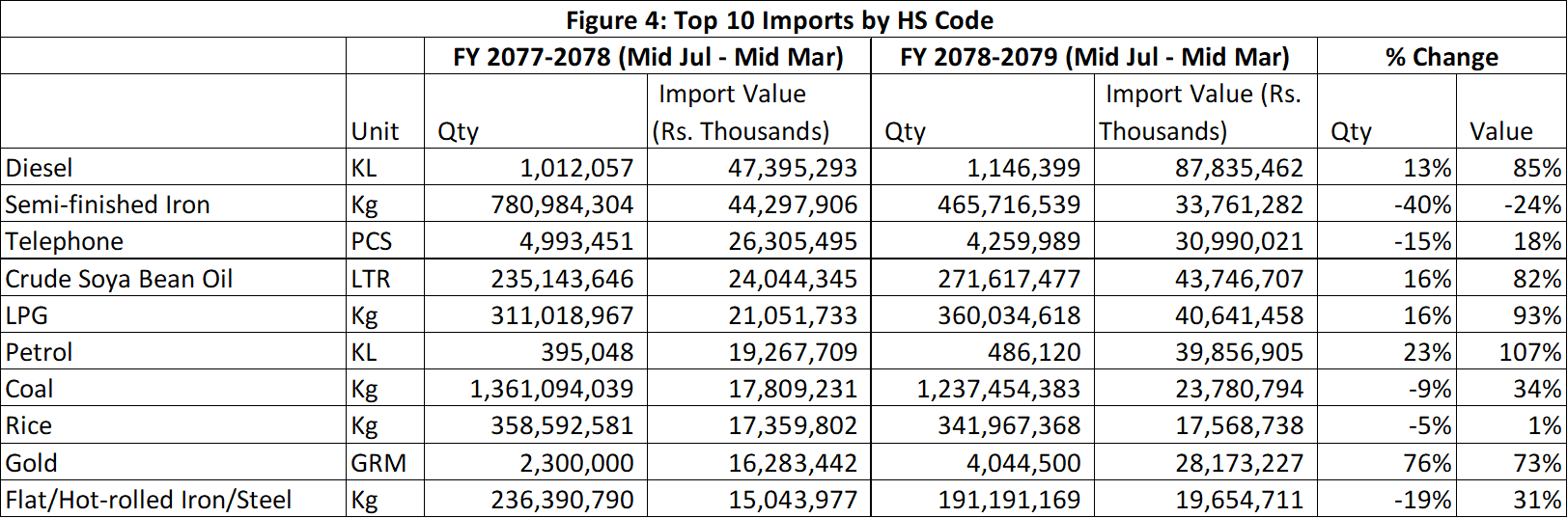

A drastic increase in the import of goods is the primary reason why Nepal’s foreign reserves have been depleting. In the first eight months of FY 21/22, Nepal’s import bill increased by USD 2.82 billion or 36.1%, compared to the same period of the previous fiscal year.

Nepal is facing the crisis of rapidly declining foreign exchange reserves. This crisis was created due to Nepal’s huge dependence on imports and years of neglect by the government to incentivize and create the local manufacturing and export capability. This article demonstrates that the foreign reserves crisis was primarily exacerbated because of the increasing commodity prices in the world, Nepal’s lack of manufacturing and export capability, and not because of any short-term reform of policy initiative by the government.

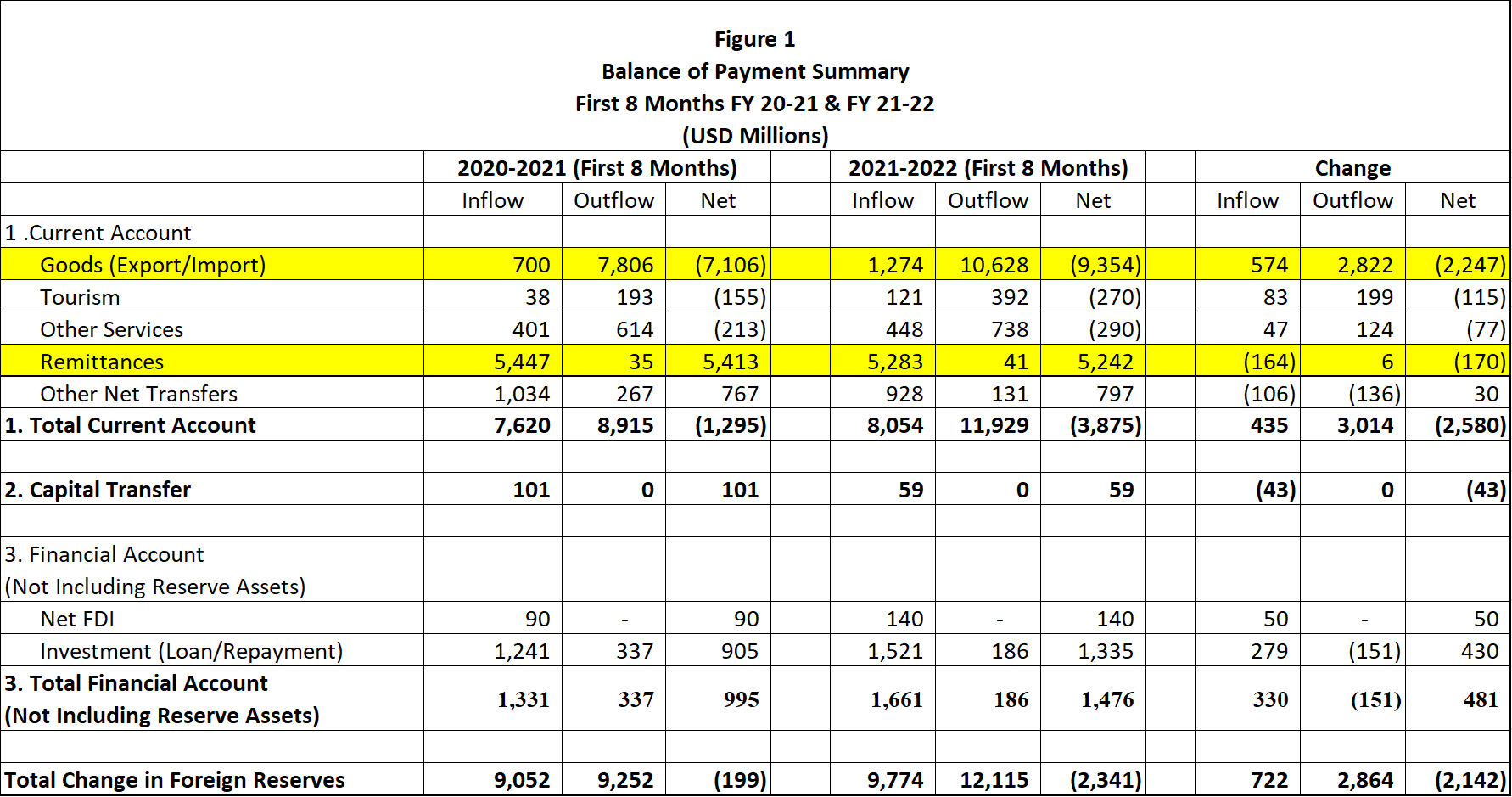

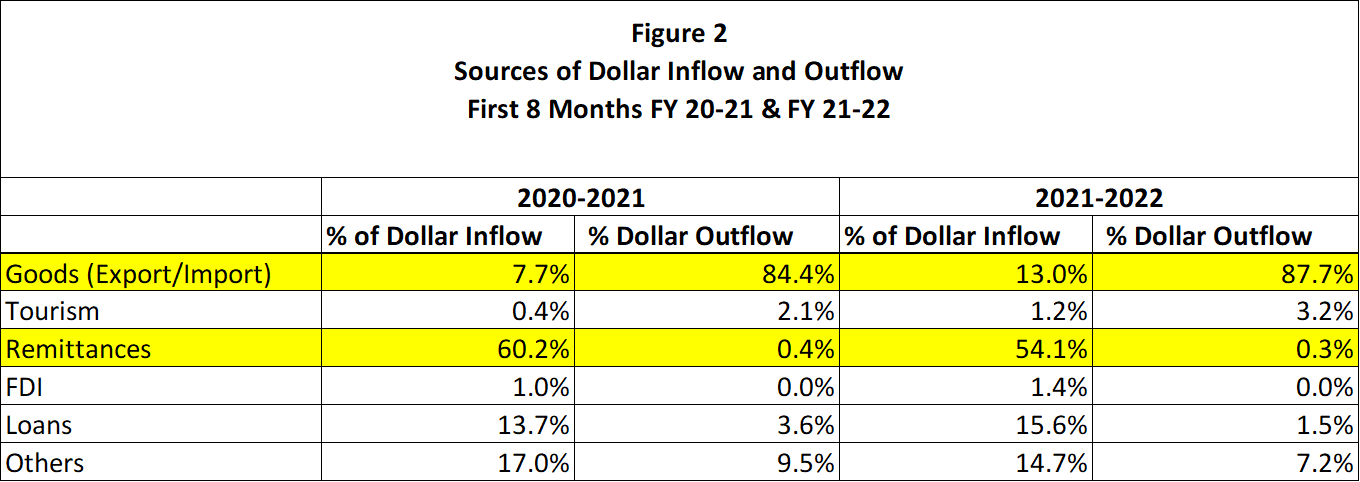

Figure 1 illustrates how Nepal accumulates and spends its foreign reserves and Figure 2 shows which categories account for the biggest inflow and outflow of Nepal’s foreign reserves. Remittances make up the bulk of Nepal’s accumulation of foreign reserves – 60.2% in first eight months of FY 2020-2021 and 54.1% in first eight months of FY 2021-2022 – and import of goods accounts for over 84.4% and 87.7% of Nepal’s dollar outflow in the first eight months of FY 2020-2021 and FY 2021-2022, respectively. A significant change in either remittances or import of goods will have a drastic impact on Nepal’s foreign exchange reserves.

As one can see in Figure 1, net remittance has fallen by around USD 170 million year on year in the first eight months of FY 21/22. Although the decline in remittance is a cause of concern, this drop in remittance was countered by an increase in exports by USD 574 million, thus the net effect in dollar inflow was positive. The major reason for the sharp decline in the country’s dollar reserve is the USD 2.82 billion increase year-on-year in the country’s import bill.

Banks have hiked their lending rates. Does that have more cons...

As one can see in Figure 3, although remittance has dropped year on year, the monthly remittance has increased by 6.77% in FY 21-22 compared to the pre-COVID times. The dramatic increase in remittance right after COVID can be attributed to Nepali workers sending more money back home to help their loved ones in Nepal navigate through the crisis and the decline of the informal remittance network (Hundi) because of various lockdown measures around the world. Since countries started to loosen their lockdowns, informal remittance channels restarted, thus a drop in remittance was expected. Although a lot of commentators have expressed their worry about Nepal’s declining remittances, this point is over exaggerated. Nepal’s demographic advantage (more younger working population) vis-à-vis developed countries will continue to allow Nepal to send migrant workers abroad and Nepal to generate remittances. The government should treat its migrant workers better by fighting for better working conditions and wages, finding new geographies, making remittances less expensive to be transferred via formal channels, and giving migrant workers better treatment when they are trying to get their passports or flying out. If the government can take a proactive approach, Nepal’s remittance will continue to thrive.

_20220416080333.png)

A drastic increase in the import of goods is the primary reason why Nepal’s foreign reserves have been depleting. In the first eight months of FY 21/22, Nepal’s import bill increased by USD 2.82 billion or 36.1%, compared to the same period of the previous fiscal year. The main cause of this increase in import is the global rise in commodity prices which has been caused by global supply chain issues, the decline in production of various essential raw materials like semiconductors, and the geo-political tensions which has caused petroleum and food prices to double. As one can see in Figure 4, the prices of nearly all of Nepal’s top 10 import items have increased more significantly compared to the increase in quantity, which indicates that the increase in prices, not quantity, is the prime cause of increasing import bills. Since there has been a significant increase in prices (over 75% in many categories) along with an increase in import quantity, the outflow of foreign reserves has had an outsized effect. If prices had remained stable and import quantity had increased, the pressure on foreign reserves would not have been as significant.

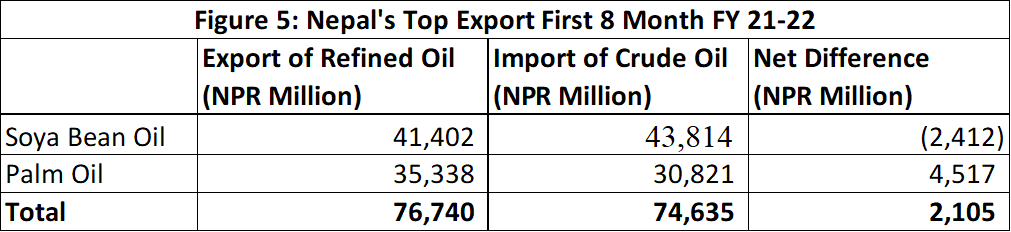

As one can see in Figure 1, there was an increase of exports by USD 574 million in the first eight months of FY 21-22. However, this figure is a bit misleading. Nepal’s top two export items are soya bean oil and palm oil. These two products account for 51.9% of Nepal’s total export. Nepal imports these edible oils, refines them, and then exports them to India because of the preferential tariff rates. Since Nepal does not produce crude soya bean and palm oil, it has to import these items to be refined. The net effect (amount paid to procure the crude oil vs the amount received after refining and exporting these oils) of these exports is only NPR 2.10 billion or around USD 20 million (see Figure 5). Thus, although the export of Nepal has grown significantly this year, the net effect of this growth is not substantial, and this export is heavily dependent on India giving preferential treatment to Nepal’s oil. Late last year, India reduced the duty it charges other countries for soya bean and palm oil, which has already caused the export of these two products to reduce.

Nepal’s government must take a proactive approach to encourage local manufacturing to alleviate its growing import bills and not only rely on short-term preferential arbitrage opportunities to increase its exports. Nepal essentially can lose 50 percent of all its exports if India decided to change its tariff rates – which should be a scary thought for Nepal’s government. It is because of years of neglect in building infrastructures conducive to manufacturing, Nepal has continued to rely on imports. Nepal’s government should introduce friendly manufacturing policies to invite both local and foreign entrepreneurs to set up manufacturing units in the country. As one can see in Figure 1, the total FDI entering Nepal was only USD 140 million or around 1.5% of all foreign reserves’ inflow in the first eight months of FY 21-22. Nepali politicians should also realize and capitalize on the fact that Nepal’s industrial hubs are right on the border of India’s most populous states (Uttar Pradesh, Uttarakhand, Bihar, West Bengal, and Sikkim) which gives Nepal’s manufacturers access to 500 million customers. If proper policies are introduced, Nepal can sell its manufactured goods to the fast-growing market of India and offset its imports bills and encourage FDI in this segment.

Finally, there is a big misconception that tourism is a big foreign currency generator for Nepal. Historically only 3 to 5 percent of Nepal’s foreign reserves comes from the tourism sector. In 2019, the average day spent by tourists in Nepal was 12.7 days with an average spending of only USD 48 a day – amounting to a total dollar inflow per tourist at USD 609.6. One could argue that airlines such as Qatar Airways, Turkish Airlines, and FlyDubai, which charge northward of USD 1,000 to bring tourists from US, Europe, and the Middle East to Nepal earn more money from Nepal’s tourism than the Nepali government. Nepal with its abundance of tourism opportunities should prioritize how to increase the per day spending by foreigners. Nepal’s government should also take steps to see how it can help Nepali air carriers to bring more tourists to Nepal so that it can also capture that inflow of tourism dollars which is now going to foreign air carriers. These two steps will allow Nepal to increase its dollar inflow from tourism and reduce its dependence on remittances for its foreign reserves.

Furthermore, although the resumption of flights after COVID will be a huge help in getting Nepal’s tourism industry running again, the flight resumptions will also lead to Nepalis traveling outside. Since Nepal is a net importer of tourism (Nepali citizens spend more money traveling outside than foreigners spend in Nepal), increasing flights is a net negative when it comes to generating dollar reserves for the country.

The net result of an increase in import bill and drop in remittances has resulted in Nepal’s foreign reserves to decline to 6.7 months in mid-February 2022 from 15.6 months in mid-August 2021 (see Figure 6). The foreign reserves of the country had increased substantially post-COVID, as imports had stopped because of Nepal’s lockdown and there was a substantial increase in remittances. However, as the economy restarted,expensive imports roared back to life which caused this steep decline in dollar reserves.

_20220416081000.png)

To curb the decline in foreign reserves, the Nepal Rastra Bank (NRB) has instituted policies of restricting imports by first asking traders to post 100% margin for all imports and then unofficially declaring that Letters of Credit (LC) couldn’t be opened for around 300 items. These policies by the NRB will help curb the foreign currency leaving Nepal, but it will also cause inflation to increase as goods will become dearer and the government will lose revenue from imports.

Approximately 35% of Nepal’s government revenues is dependent on customs duty and the VAT and excise duty that it collects from the import of goods. The drop in imports because of NRB’s policy will significantly impact Nepal’s revenue collections, which will have a ripple effect on the economy as the government will have to reduce its already low capital spending. Depending on how long the import ban lasts, it could also cause unemployment to increase as traders will have to start laying off employees as there will not be any goods to sell.

Nepal’s policy-makers are caught in a catch-22 situation - by restricting imports they will increase the foreign reserves of the country, but this will also lead the country toward a period of high inflation, low government spending, and possibly increasing unemployment. The recent suspension of the NRB Governor, who is responsible for Nepal’s monetary operations, further creates uncertainty at a time when the government officials need to be working together to create policies which will help strengthen Nepal’s economy.

The best-case scenario for the government is to hope that the commodity prices start falling soon and the increasing exchange rates encourage migrant workers to send more money back home. For this to happen, international shipping prices must stabilize, and the geo-politics has to improve. Unfortunately, Nepal’s government is at the mercy of international supply shocks, and not any of its own policy, for any significant improvement to happen in the economy. Short-term policies like limiting imports will help, but it will be putting a band-aid on a problem that requires surgery.

As it was mentioned in the introduction, the current foreign reserves crisis in Nepal is not because of any policy that the government has recently implemented, but because of its long-standing apathy to improve local manufacturing capabilities and promote Nepal as a place for high end tourism. A crisis can be used as an opportunity by the governments to learn from its past mistakes and make meaningful reforms. We can only hope that the government officials understand why the foreign reserve crisis was created, and take proactive steps mentioned above to solve the problem.